Your Project's Philosophy: Why Just "Story" Isn't Enough

There is a lot of talk and a lot of media coverage about the idea of a “story” for a project. It’s the hot topic everyone clamors to in search of finding the new, new thing. But from my perspective, what if the more important thing isn’t the “story” at all? What if the more important thing is a Project Philosophy? Let me show you how a unique guiding philosophy can allow each and every project (storied or not), to run more smoothly and to become exactly what everyone envisions.

I've been working in this industry for over three decades. In that time, I've been on some really great projects with some really fantastic project teams, and I've been on some that were not so good. In that three decades, it just always struck me that if we could only have all those great characteristics rolled up into one team, and propel that forward from owner to owner and from project to project, what amazing projects we could create. That's the genesis of this best practice – Project Philosophy.

As a veteran hospitality professional, I’m also struck by the immense amount of time owners, operators, architects, designers, and manufacturers spend in order to protect themselves. Owners spend voluminous time vetting architects, designers, and manufacturers. They hire a Project Manager to help guide the process and help orchestrate the symphony of consultants and variables. Operators constantly work to ensure that the brand standards are met and maintained, that the operations of the property runs smoothly and efficiently. Architects spend time on testing, siting, engineering, documentation. Then there are the contracts, legal fees and time, detailed written specifications; the list is long. What are we protecting, and from whom?

I think that there's probably a general understanding shared amongst us, but yet we all have our own focus based on our discipline, based on our unique concerns.

We all know what we risk by not being protected. Risk comes in all shapes and sizes, from lost revenue, blown budgets, schedule overruns, compressed schedules that affect manufacturing or require excessive design manpower. And then we've got far more serious things like legal ramifications. There can be all kinds of things that go wrong.

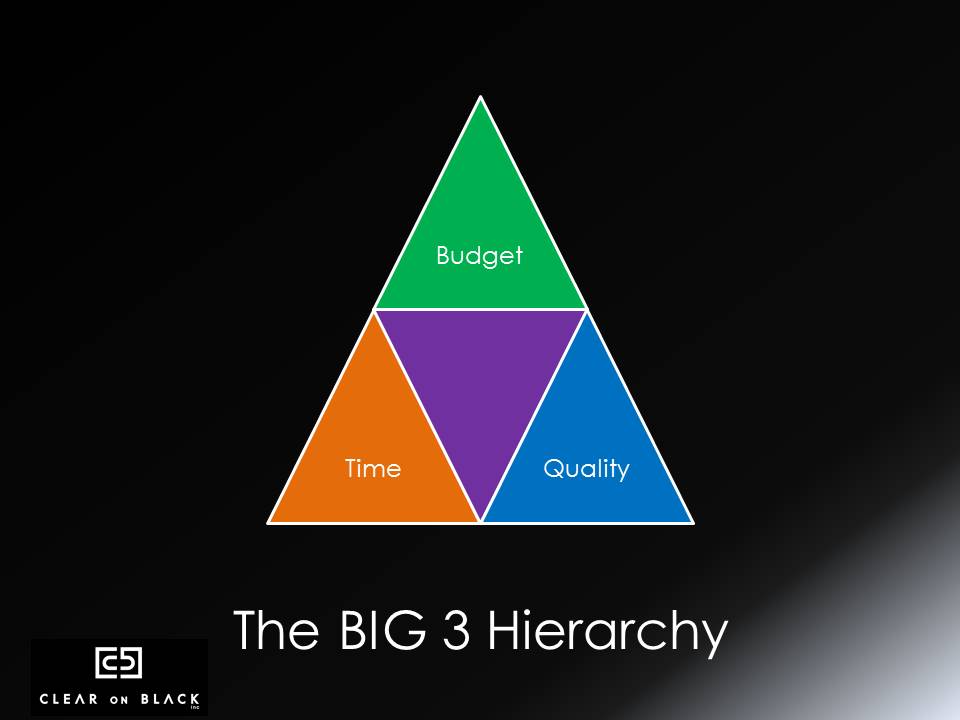

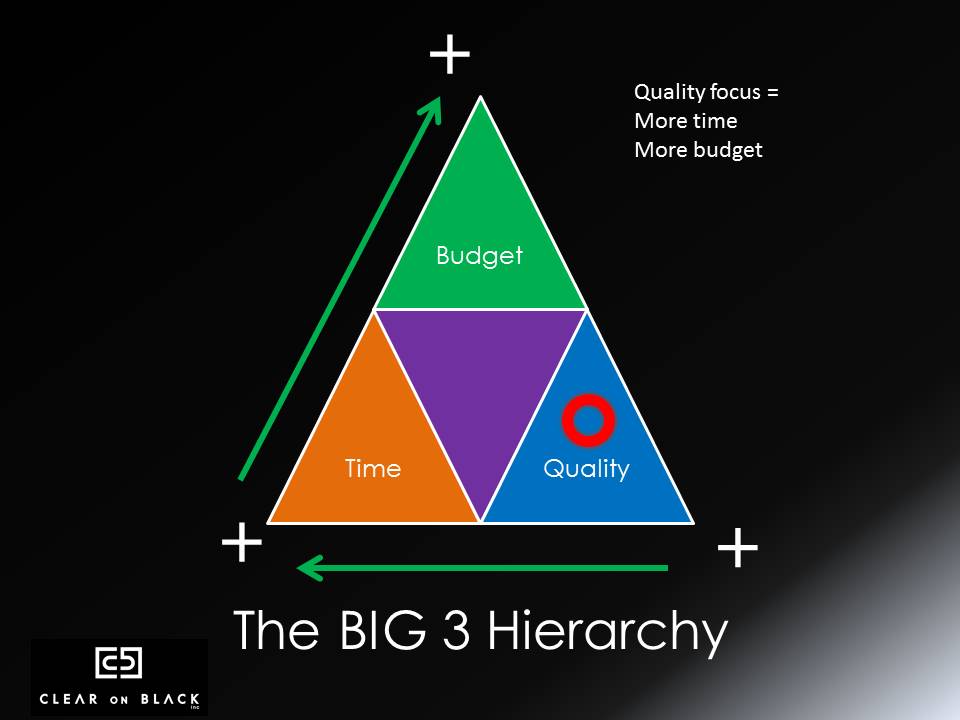

I started asking myself, "What are those things that really either swing a project to the positive or pull it to a negative?" Over time, I’ve been able to narrow it to three key characteristics: budget, quality and time. In my own design firm, we call those the BIG 3. The “Big 3” is the basis of Project Philosophy, and trust me, every project has one. The important distinction is that some project teams establish and communicate the Philosophy at the outset, and some project teams just let the Philosophy happen, which in my experience, can disempower the project.

So the first characteristic of the Big 3 is budget. Obviously, budget jobs are ones that have unusually tight budgets. Rarely do you ever see a job where the team is told, "Spend everything you possibly can." The second characteristic is quality. Quality is usually not how poor the quality can be, but it's a focus on how high the quality can be, quality of all kinds of things from the FF&E, to the materials used, to the dynamics of the built physical spaces. The third characteristic is time. Rarely do you have an instance where somebody says, "Take all the time in the world. It doesn't matter; there's no schedule."

What is really interesting is when one of these three key characteristics starts to become more dominant than the others, because all of a sudden, the other two start to shift in response to it. These aren’t three static characteristics, but rather three very dynamic characteristics. Once you know what they are and what they do and how they behave, you're in a far better position to be able to have a smooth running project and one that is predictable and that will start to behave better. You will be able to influence with volition how a project flows throughout its evolution from beginning to completion.

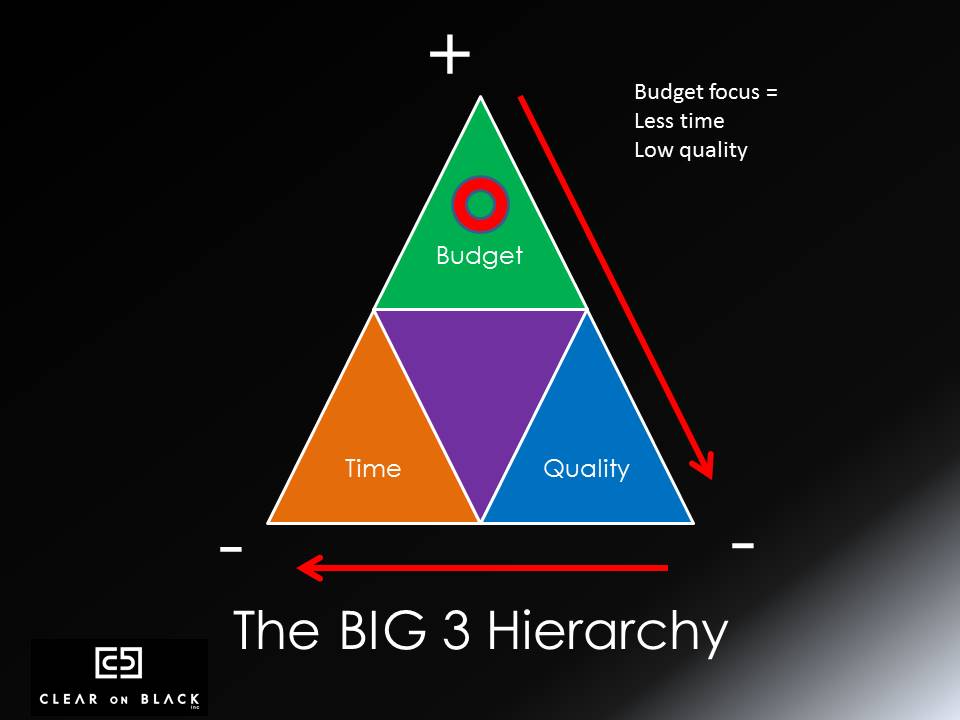

Let's take a look at an example of what I mean. Let's say that on our project, budget is the primary focus.

We were brought into a guestroom renovation project that had been designed about two years previous. It was done under a very, very tight budget. This budget dictated that the owner and the purchasing agent make certain decisions in selecting fabricators and manufacturers for the FF&E. What happened was, yes, they all met the budget. Yet in order to do that, there were a lot of concessions and compromises, some of them known, some of them not known, even though there were prototypes of various FF&E pieces.

When we were commissioned now two years down the road in what should have been a 12-year casegood life cycle, there were premature failures across the board. It was softgoods. It was casegoods. It was light fixtures. It was decorative lighting. It was draperies. What had looked to be great savings up front and a significant dial-down on cost ultimately really wasn't any savings whatsoever.

If you're an owner with a fix and flip strategy, this works great. It's a perfect short-term solution. And it will, ultimately and probably, be somebody else's problem. But if you're a company or you’re an individual that holds your assets for a longer time, then it's maybe not the most prudent approach.

The point of the BIG 3 is to knowingly and intelligently assess and consider the pluses and minuses. Being aware of the ramifications, the risks, and the possible rewards puts you in a far better position to make informed decisions. Train your internal team, train your project managers, train your entire consultant team how this is going to impact them.

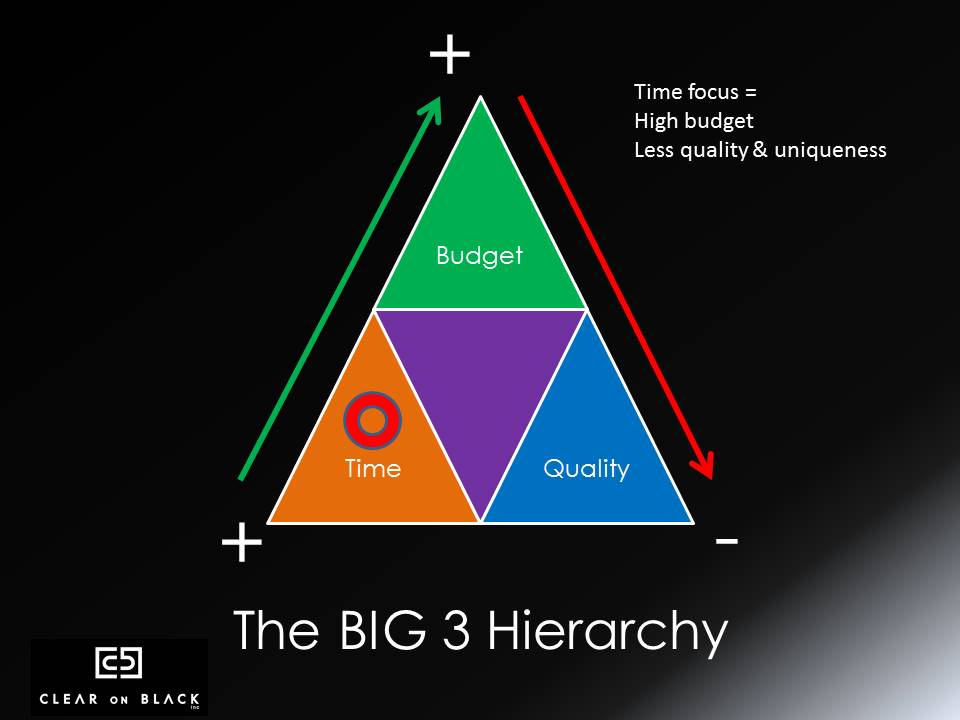

The next factor is time. If time is the focus, and I’m talking extraordinarily tight time frames, what happens? What happens to budget and quality? To give another real life example, we were commissioned for a large suites renovation that had to be done in an extremely tight time frame. We asked and received clear direction from the owner. We all agreed that certain criteria had to be met. And the number one focus was time. Budget not so much. So here's what happened. All of a sudden, we were basically relegated to in-stock FF&E items. So that meant limited resources. We were essentially buying off of showroom floors with the inability to make any custom adjustments or changes. That, for us, in the upscale and luxury market, is a big deal because our clients come to us because they want a tailored look; they expect a bespoke appeal. They want special. But when you're buying in-stock with limited resources, you just simply cannot make any of those kinds of changes. It's all about what they have in stock.

And there's another factor. If you're buying off the showroom floor, it is likely residential-grade product. Why is that a big deal? Fire codes and double rubs come to mind right off. Commercial hospitality performance criteria are paramount when it comes to meeting brand standards and applicable codes.

I know of a hotel that was fully furnished with 100% residential grade furniture. It was over-scaled, to an almost cartoon-like level. It was oddly proportioned, and it wasn't tailored, yet it was trying to fit in a luxury market position. It simply didn't meet the standards. So back to those pluses and minuses. Understand that if time is a serious factor, the minuses are lost uniqueness, inability to manage scale, sizing, and proportion, and possibly a much higher cost than was necessary. This can be a challenge in the upscale and luxury market, where owner, operator and guests alike have an expectation. It's our job as designers and project team members to deliver on that promise. It comes in very subtle ways.

The third characteristic is quality. Everybody wants it to be wonderful, right? Everybody wants to spend good money and get great projects and have great detailing and have wonderful features and the most expensive fabrics. That scares most owners because they assume that everything is going to be expensive. If you're doing a palace, yeah, then everything probably should be expensive, but if you're not, and most of us don't, then I believe that in designing responsibly, you need to strike a balance. You need to create the look, the appeal and the feel of high quality and luxury without, necessarily, making everything equally and unnecessarily expensive.

What striking that balance means is a change of focus in order to achieve quality without overspending. I think largely it’s planning up front with foresight. And the good news? Front-end planning is free. It is a little bit of head time with the right people, figuring out what you’re going to do. What you’re going to plan for. How to evolve this so that you get the most quality that you possibly can. But then, how do we then execute that? In my mind, execution is driven by the quality of the documentation. That is project team wide – a holistic approach. It’s from the architect, the ID as well as all the sub-consultants, and all the trades. It's creating a package involving the general contractor so that it’s something that he has seen before. He has been instrumental in its evolution; there are no surprises. When he takes that to the street, he has confidence that he knows what's going to happen with it and how to work with it.

The quality documentation also applies to the FF&E because if we're designing specialty pieces, we're doing amazing detailing, stitching and custom light fixtures and things like that. The quality of the documentation has to be there, too. You can't in good conscience ask somebody to fabricate a unique, complex and beautiful chandelier that is based on a lame fixture cut that you caught off of Pinterest. That’s simply not responsible design. And to hang that on a purchasing agent to “make it biddable or to make it real” is ridiculously irresponsible.

We did a resort project which was straight out of the gate understood to be very, very high quality. The owner said, "Okay. We need to plan this." He made a really smart move because he knew that the construction cycle and the planning cycle were going to be long. What did he do with that time? He started doing early buyouts on materials, on the plumbing, on the Italian cabinetry and the GC light fixtures. He was able to warehouse all those various materials and components for a year and a half on an early buyout, and he saved over $2 million dollars.

When the general contractor was brought in, they, the ID team, the architect, all the sub-trades, everybody was rowing in the same direction because we all understood from the owner what the Project Philosophy was from the outset. Eight years later, TripAdvisor says this same property is an absolute leader in the market. (There is nothing like the brutal honesty of Social Media to tell you how your past projects are perceived and how they are doing). It is wearing very well from an operational standpoint because, yes, we asked for and received operational input with the operator up front. We knew what things were going to wow people, and, yet, we didn't want them to wear out either.

This client did a great job of developing and expressing the Project Philosophy to the team, down to the sub-trades.

From time to time, the reality is that the Project Philosophy must change should issues arise, but overall, that hierarchy of the Big 3 should remain as constant as possible. The caveat is this: nobody but nobody, except the owner can reshuffle the deck. Nobody else has the authorization. Nobody else has the control. That is strictly an ownership role. That constant settles the team, and they understand. And again, should the change in Project Philosophy be required, it’s essential for the owner to communicate it to the team.

Interestingly, another attribute of establishing a well-articulated Project Philosophy ends up assisting ownership in hiring consultants appropriately. And actually, it's not so much just consultants, it applies to the other stakeholders in the project as well. Consider that certain people and certain firms on the design side are geared to budget-oriented projects. Some are better at speedy delivery. Same thing with quality. Some firms are better at quality. Same thing goes for manufacturers and fabricators. Some don't do large quantities; some do one-offs much better than big bulk orders. Some are better at quality, etc. Just remember the balance and the interplay between the Big 3.

To come full circle, one of the simplest, most inexpensive, least time-consuming ways to mitigate risk on a project is for the ownership team to agree on their Project Philosophy and the hierarchy of the Big 3 and express it to the project team early and often. Then as new consultants are brought on board, as sub-trades are brought on board, as new elements are brought on board, the Project Philosophy becomes the compass to guide the team, and it actually becomes self-generative and takes on a life of its own.

There is a lot of talk and a lot of media coverage about the idea of a “story” for a project. It’s the hot topic everyone clamors to in search of finding the new, new thing. But from my perspective, what if the more important thing isn’t the “story” at all? What if the more important thing is a Project Philosophy? A unique guiding philosophy which allowed each and every project (storied or not), to run more smoothly and to become exactly what everyone envisions. That’s what interests and inspires me.

Like this article? Sign up for our thought leadership Blog Digest & Newsletters and continue to learn from us.